What’s the deal with fanned-fret guitars anyway?

Multi-scale guitars, fan-fret guitars, fanned-fret guitars — call ’em what you will, these strange-looking axes have understandably caused more than a few guitarists to raise their eyebrows in bewilderment, disbelief, or both. The purpose of this short article is to (hopefully) explain the “what,” “when,” and “why” regarding these fine six-, seven-, and even eight-stringed instruments to those still somewhat mystified by them.

As bizarre as a multi-scale guitar may first appear, I’m sure you’ll be relieved to learn that the subject of multi-scale is not as scary as you might think. In fact, dare I say it, it’s actually quite logical. It’s also nothing new either — the idea’s been around for literally ages, as you’re about to find out. First though, let’s define exactly what the adjective “multi-scale” means.

Multi-scale Musical Instrument: One where every string has its own individual scale length. The lower the string’s pitch, the longer its scale length is.

Example: Piano, harp, or multi-scale guitar.

Seems pretty straightforward, right? As a picture often paints a thousand words, let’s take a quick look under the hood of a grand piano.

And, while we’re on the subject of definitions, let’s quickly do the same for “scale length” to make 100% sure we’re on the same page:

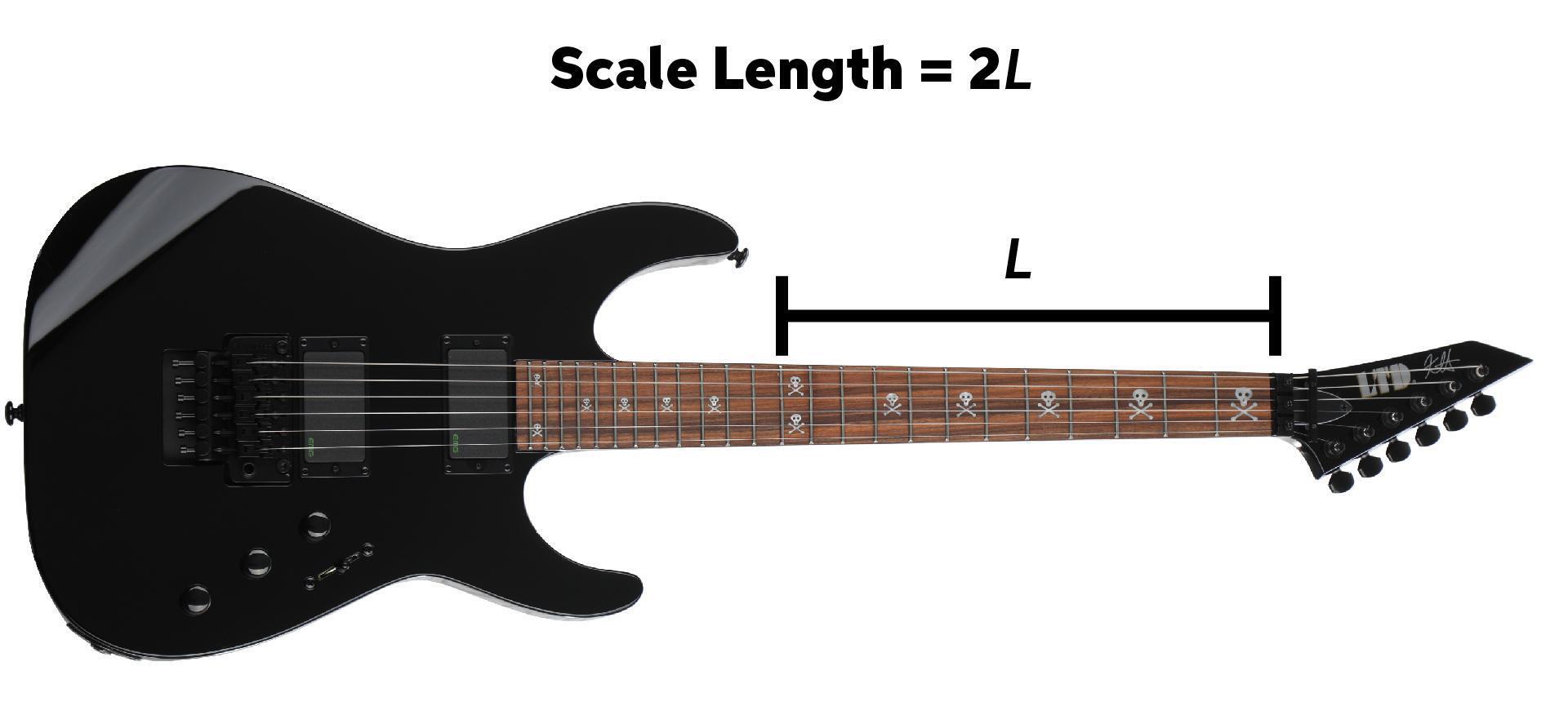

Scale Length of a guitar: The simplest definition is that it’s the distance between a guitar’s nut and bridge. The more exact definition is this: “Measure the distance from the front edge of the nut (where it butts up against the end of the fretboard) to the center of the 12th (octave) fret, then double it.”

In the case of the “traditional” electric guitar — all six (or seven or eight) strings share the exact same scale length. That said, as I’m sure you’re aware, not all scale lengths are the same. For example, a Gibson Les Paul has a scale length of 24.75 inches, while a Fender Strat has a scale length of 25.5 inches. There are also shorter and longer scales, as well — from kids’ guitars (e.g., 22 inches) to baritones (e.g., 27.7 inches), respectively. And, as we’ll get into shortly, scale length impacts string tension and tone plus a couple of other things, too.

Definitions done, let’s go back in time…

Multi-scale Fretted Instruments: The Story So Far

As already mentioned, the concept of a multi-scale stringed instrument is nothing new. The piano was born in the early 1700s, and, according to historians, the harp has been around since 2500 BC! As the guitar has frets though (granted, my pal Ron Thal, a.k.a. Bumblefoot, might disagree!), let’s take a quick look back at fretted-instrument history via “the Googles” and “internets” and see what we can find out in terms of multi-scale…

The weird- and wonderful-looking fretted instrument shown above is called an Orpharion, which emerged in the 16th century. And, as you clearly see, its bass strings are longer than their higher siblings, and the frets are definitely “fanned.” Yep, this is nothing new. That said, a patent for such a fretboard wasn’t filed until a couple of hundred years later, in 1900. Makes one wonder if “djent” was first invented centuries ago, too?

Short history lesson over. Now that we know the “what” and the “when,” let’s look into the “why.”

Why Multi-scale Makes Sense

Here are a few rules of thumb that will help explain why multi-scale makes sense.

Scale length impacts string tension… and “bendability”

The longer the scale length, the tauter (tighter) a certain gauge of string will be when in tune, and vice versa. For example, a .017-gauge G string on a Gibson Les Paul (24.75-inch scale length) will be looser than it would be on a 26.5-inch scale Schecter 7-string. This means that the G string on the Les Paul will be way easier to bend than the same string-gauge string on the Schecter 7-string.

Scale length impacts tone… especially when tuning way down

While there’s an undeniably cool sound and feel to a string that’s a little on the loose side, I’ll quote the immortal David St. Hubbins of Spinal Tap here: “There’s such a fine line between stupid and clever.” There comes a point where, no matter how thick your strings are, if you’re trying to tune down a 25.5-inch-scale-length guitar all the way to B, they feel like spaghetti and start to sound equally flaccid and lifeless, too. And, as a result, the strident “djent” you desire when you chug a palm-muted low-string note is nothing more than a dull, indistinguishable, and floppy “ooff.” This highly unwanted and unwelcome tonal state of affairs is known as SSS — Spaghetti String Syndrome!

NOTE: To add insult to injury, not only do tuning and intonation become a nightmare, but there’s a good chance that the thicker low-E string you’d like to use will be too big to fit in the hole in your “regular” guitar’s tuning peg.

The reason why thick, low-tuned strings sound better on longer-scale guitars is a scientific one, and it all has to do with frequency and the ways strings vibrate. The lower the string’s pitch, the lower the frequency and the longer the wavelength. Check out the below diagram, and all will be revealed…

So, logic tells us that, for low-frequency notes, the longer the string is, the better. This, my friend, is why bass guitars have a much longer scale length (e.g., a Fender P Bass is 34 inches), ditto the aforementioned baritone axes and 7-strings, too (e.g., a Jackson Misha Mansoor signature 7-string is 26.5 inches), as the low string is tuned down to B — or even lower. The goal is simple — to avoid Spaghetti String Syndrome at all costs!

Simply put — thicker, lower-tuned strings sound better on longer-scale guitars,especially when extreme tunings such as Drop A or even Drop G are being used. If you don’t believe me, please take another look at the photo of the grand piano above… or of the harp below.

As you can see in the colorful picture above, the thicker and lower in pitch the string is, the longer the scale length. Simple science, right? But wait, there’s more! The opposite is also true…

As counterintuitive as it may first seem, thinner, higher-pitched strings sound better on a shorter-scale guitar than on a longer-scale one. It also makes sense in terms of tension. Huh? What? Let me explain…

For thinner, higher-tuned strings, the extra scale length results in a tautness that not only makes said strings difficult or uncomfortable to bend but that can also make them sound harsh and shrill rather than rich and full. Once again, we risk crossing Spinal Tap’s fine line that lurks between clever and stupid.

So, to summarize, longer scale lengths are better for thicker, lower-tuned strings; while a shorter scale length better suits the thinner, higher-tuned ones.

Scale length determines the distance between the frets on your guitar’s neck

Obvious? Absolutely, yes! That said, it shouldn’t be overlooked, as it definitely impacts playability. For example, while that wide-stretch, Eddie Van Halen “Beat It” lick that has you stretching from the 12th fret to the 19th fret on the high-E and B strings might be doable on your 24.75-inch-scale-length Epiphone SG, it might well be literally out of reach on your ESP 27-inch baritone… unless you have spider fingers, of course!

Scale length impacts tuning stability and intonation

Have you ever tried tuning and playing a regular-scale guitar that’s tuned way, way down? I’ve played a 25.5-inch-scale guitar tuned down to B (B, E, A, D, F#, B), and, even with really thick strings, keeping the thing in tune was an absolute nightmare. The low strings were so loose that, if you picked them too hard, they’d go sharp on first impact. Sustain and “cut” suffered, too. Switching to the same tuning on a 27-inch-scale baritone fixed that issue, but soloing was no fun — bending strings felt a little weird, and some wide-stretch runs were literally impossible to reach.

In short: tuning and intonation both improve with a longer scale length when dealing with thick, low-tuned strings. In the case of the thinner high strings though, a longer scale length is definitely not “shred-friendly.”

And last, but certainly not least…

Ergonomics — the way your fretboard hand naturally moves

From the very first time we pick up a guitar, we’re taught/programmed/conditioned to move our fretboard hand in a perpendicular fashion across the neck so our fingers are at a right angle to the strings, just like the frets. While this feels comfortable in the middle of the neck, it becomes less so nearer to the nut, and it definitely doesn’t feel as comfortable when traversing the higher regions of the fretboard — try barring all six strings with your index finger at the 15th fret, and you’ll feel what I mean. Your fretboard hand’s wrist is forced to supinate (to rotate away from your body’s central line, which feels uncomfortable when your arm is in that position. It is, in fact, much more comfortable and also more natural-feeling to rotate your fretboard hand’s wrist in the opposite direction (toward the body’s center line) — a movement called pronation.

A barre chord at the 15th fret on a “regular” 7-string guitar, and the same exact shape played on a multi-scale. The latter feels more comfortable, as the wrist is pronated rather than supinated.

The fact that pronation has a lot more rotational capability than supination also plays a factor. Try it by mimicking the below trio of photos with your fretboard hand facing upwards, and you’ll see and also feel exactly what I mean. Photo A is with no wrist rotation; Photo B is maximum supination; while Photo C is pronation maxed. As clearly indicated — supination is an extremely limited movement.

This, IMHO, is exactly why you’ll often see players such as Zakk Wylde and Slash rotate their guitars so that the neck is almost vertical when they’re soloing higher on the fretboard. Doing this allows them to pronate their fretboard hand’s wrist — making for much faster and more comfortable shredding. Make sense? A fanned-fret axe will allow you to do that without having to throw a cool-looking “guitar hero shape!”

The converse is also true the nearer to the nut you get. When playing a barre chord at the first or second fret, you’ll invariably find you have to bend your wrist pretty much to the max in order to do so. Believe it or not, on a multi-scale guitar, chords like that are easier to play since your wrist will stay straighter and also tend to supinate… if you let it. Not all do — old habits (and muscle memory) die hard!

If all this pronation/supination talk still isn’t making sense yet, quickly try doing this: If you put your fretboard hand in the usual, perpendicular, “about to play a barre chord” position without a guitar neck there then relax and move your hand toward where the nut would be, your wrist/forearm will naturally tend to supinate (rotate away from your body) a little. And, when you do the same thing in the other direction — namely, go higher on your imaginary neck — your wrist/forearm will do the exact opposite and naturally tend to pronate (rotate toward the body) quite a bit. If this logic makes sense to you, then so will the way the frets are fanned on a multi-scale neck. It’s all about ergonomics.

Multi-scale: Combining the Best of Both Scale-Length Worlds?

As you can clearly see by merely looking at a multi-scale guitar, the logical thinking behind it is to offer the player the best of both worlds in terms of scale. The scale length is shortest on the highest (thinnest) string and longest on the lowest (thickest) — thus mixing and matching the tonal and playing advantages of both. You get high strings that are a breeze to bend and shred on and tight, full-sounding low strings that intonate and tune like a dream.

In addition to obvious factors such as finish, features, and aesthetics, two other key things to consider when shopping multi-scale guitars are:

- The scale lengths of the highest and lowest strings, as they can vary from manufacturer to manufacturer. Take these three 7-string multi-scale offerings for example — Jackson X Series Dinky DKAF7, Ibanez RGMS7, and Strandberg Boden Metal 7. The Jackson and Ibanez both go from 25.5 inches to 27 inches, while the Strandberg goes from 25.5 inches to 26.25 inches.

- The position of the so-called straight fret — a point that is sometimes referred to as the “neutral point.” As its name suggests, the straight fret is the one that’s perpendicular to the strings, while all those around it literally fan away from it in both directions. On some multi-scale guitars, the neutral point is around the seventhfret, while on others it can be as high as the 12th. I’ve even seen a multi-scale axe with its neutral point at the nut. The designated placement of the straight fret will obviously impact the way the fretboard plays and feels both above and below it due to the resulting “fret fanning” pattern it instigates.

Multi-scale Math & Science

The math and science behind multi-scale are beyond the scope of this particular piece — and perhaps the limited capabilities of my gray matter, too. If you’re interested in learning more about the exact nature of fret-fanning formulas and how the frets are meticulously measured and placed, then there’s a bunch of great articles, videos, and tutorials about it on the internet. That said, there’s also some less-than-stellar stuff out there since literally anyone with a smartphone and a pair of thumbs can post on blogs, write articles, and even put “expert” videos up on YouTube. So, click with caution, my friend… click with caution!

Conclusion

A well-designed multi-scale guitar offers you the advantages of various scale lengths while removing many of the disadvantages. You get fat, punchy low notes; singing high notes; and bendable thin strings where wide, shred-approved fretboard stretches are still reachable. Plus, metal-approved, “lower than whale droppings” (© Clint “Dirty Harry” Eastwood) tunings are possible without the tuning and intonation problems a regular-scale, non-baritone guitar might present.

Obviously, multi-scale guitars — be they six-, seven-, or eight-string — aren’t for everyone. To some, they’ll just look too darned weird, while others will always take the well-trodden, traditional-axe path without even a sideways glance… and it’s all good! As an old adage I like to use a lot so wisely states — one man’s meat is another man’s poison.

I’d like to close by saying this: When a multi-scale-playing friend told me that I’d be surprised at just how quickly I’d get used to the seemingly weird fret angles, I was more than a tad skeptical. He was 110% correct though — after a mere 15 minutes of noodling on a Schecter Silver Mountain multi-scale 7-string, I forgot all about the “strange” fret angles and had a blast in both riff/rhythm and solo/shred modes.

As many folks much smarter than me so often preach: never judge a book by its cover! Regardless of your possible reluctance, I dare you to pick up a multi-scale axe and give it a go. The experience might well surprise you… pleasantly!