What exactly does “harmony” mean? Well, according to “the Googles” (courtesy of Henry Rollins), here are two pretty quaint definitions:

- The combination of simultaneously sounded musical notes that has a pleasing effect.

- A pleasant musical sound created by different notes being played or sung at the same time.

I’ve always been a sucker for two guitarists playing single-note lines in unison that have a “pleasant musical sound.” Wishbone Ash’s clever dual-guitar harmony work got me interested, and then along came Thin Lizzy, and I was 110% hooked. From classic cuts such as “The Boys Are Back in Town” to lesser known tracks such as “Old Flame,” Lizzy’s hook-laden guitar harmony lines proved to be the proverbial icing on the cake. Yes sir, the effect was indeed “pleasing.”

As a result, Thin Lizzy is rightfully regarded in the minds of many as true masters of this dual-guitar art, and the band’s influence can be heard in many popular acts, especially British ones, such as Def Leppard and Iron Maiden.

The $64,000 question is, how do you come up with a complementary harmony line to a cool melodic single-note melody?

Thankfully, as I eventually discovered in my youth, it’s actually not that difficult. It can’t be — I can do it! Here’s the skinny…

Creating a Harmony Line in a Minor Key

Why minor? Because most rock and metal songs are written in minor keys, that’s why! “Why minor as opposed to major, though?” I hear you ask. Well, simply put, major keys sound jolly and happy, while minor keys sound moody and mean. And while “happy” and “metal” are hardly synonymous, “mean” and “metal” are. So in most rock songs, the use of a minor key or three is a given! Make sense? Good.

A goodly amount of rock and metal songs — particularly those that have a melodic as opposed to a malevolent bent — are based on what is known as “the natural minor” scale: the moveable fretboard pattern shown in figure 1. For the sake of convenience, we’re going to look at A natural minor. We’re going to do this for two very sound reasons:

Figure 1

- An awful lot of rock and metal songs are in the key of A minor, and the fact that it is the second-thickest open string note on a (6-string) guitar is not a coincidence. Chugging away on that open string note is a great thing, especially when healthy helpings of overdrive and palm-muting are applied!

- The notes in A natural minor happen to all be “whole notes” — namely, the white keys on the piano: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, etc. And this means there’s none of those pesky sharp (#) or flat (b) notes in the mix.

What we’re going to suss out in this little lesson is how to find a diatonic third harmony note to any note in the A natural minor scale. And providing you know the scale pattern (see figure 1), can count, and know the alphabet, it’s literally as easy as “1, 2, 3.”

What on Earth Does “Diatonic Third” Mean?

Now at this point, you’re probably thinking, “Well that’s all well and good, but what on earth does that fancy ‘diatonic third’ term you just unleashed mean?” Let me explain.

When used in this context, “diatonic” simply means “only involving notes within the key or scale being used.” So in the case of A natural minor, A, B, C, D, E, F, and G are the only “diatonic” notes in town.

As for “third,” as the name suggests, it means the note a third higher in the scale (remember, “diatonic” dictates that we’re staying strictly within the scale) being used. Here are two quick examples that will hopefully explain:

- Let’s say we want to find the diatonic third of the note A. As we already know, the A natural minor scale goes as follows: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. So if A is our first note, the third will be the note two higher in the scale, which is C. Make sense?

A = first, B = second, C = third.

Got it? Let’s double-check.

- Now let’s find the diatonic third of the note E within A natural minor. Thanks to my profound knowledge of both counting and the alphabet:

E = first, F = second, G = third.

So G is the diatonic third harmony note of E in A natural minor.

Told you it was pretty easy!

“A, B, C… Easy as 1, 2, 3”: Creating a Diatonic Third Harmony Line

Shameless, cheesy Jackson 5 lyrics quote aside, let’s get to it…

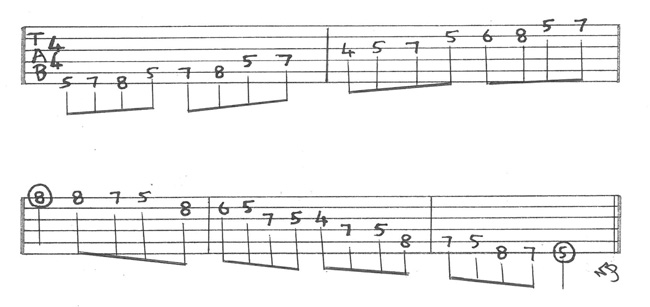

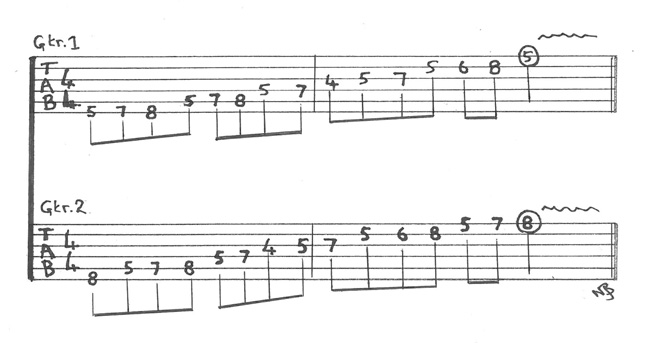

Let’s say I want to harmonize the A natural minor scale played ascending over two octaves as shown in figure 2, Gtr. 1. All I’d have to do is play a unison, 2-octave ascent of the same scale that starts a diatonic third higher. So, I’d start and finish on C as shown in figure 2, Gtr. 2. Pretty simple stuff, and as the accompanying video illustrates at 3:42, it sounds cool too — even though all we’re doing is climbing the A natural minor scale.

Figure 2

Now, let’s continue to mirror the video and quickly work out the diatonic third harmony of the short A natural minor run shown in figure 3.

Figure 3

The notes I want to harmonize are E, F, C, and D. So once again, utilizing my counting and alphabetical abilities, the harmony notes are as below:

| NOTE I WANT TO HARMONIZE | DIATONIC THIRD HARMONY NOTE |

| E | G |

| F | A |

| C | E |

| D | F |

Figure 4 shows the two lines together: Gtr. 1 is the “main guitar” part, and Gtr. 2 is the “diatonic third harmony” line. Not too hard at all.

Figure 4

But wait, there’s more…

All Natural Minor Diatonic Thirds Are Either Minor or Minor Dyads!

A while back, I did a video entitled Five Famous Rock and Metal Riffs Using Major and Minor Dyads, which relates to this. Just to recap:

Dyad = two different notes played together in unison (at the same time)

Major Dyad = two notes played together at the same time that are two tones apart (e.g., four frets apart on the same string) — for example, C and E.

Minor Dyad = two notes played together at the same time that are three semitones apart (e.g., three frets apart on the same string) — for example, A and C.

As it just so happens, every single diatonic third harmony interval in the A natural minor scale is either a major or minor dyad. Check it out…

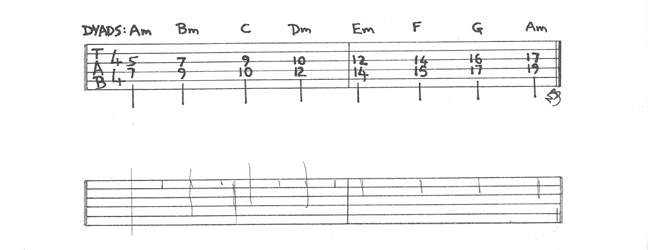

Let’s ascend the A natural minor scale one octave on the D string (from A at the seventh fret to A at the 19th fret) while playing the diatonic thirds of each note at the same time on the G string. The resulting ascending dyads are A minor, B minor, C major, D minor, E minor, F major, and G major as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5

And that reveal leads us nicely into…

Working Out Diatonic Third Harmony Lines “the Dimebag Way”

As mentioned in previous inSync articles, I had the extremely good fortune to work with the late, great Dimebag Darrell on his long-running and incredibly popular “Riffer Madness” monthly column for Guitar World. We also wrote a book together based on said articles. Dime’s musical thought process included two simple but powerful philosophies:

- The only scale you need to know is the chromatic scale!

- If it sounds right to you, then it is right.

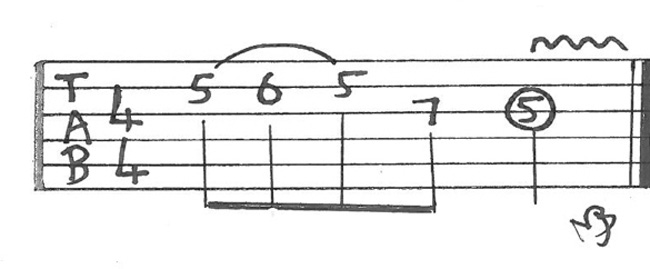

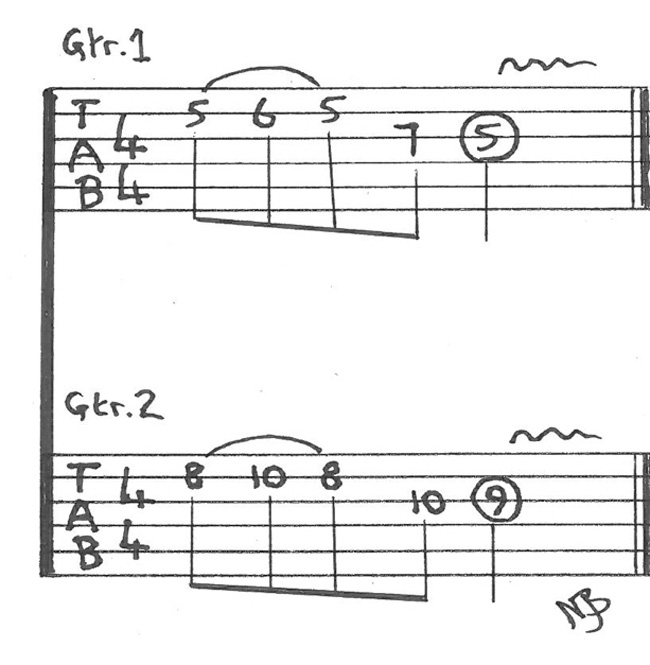

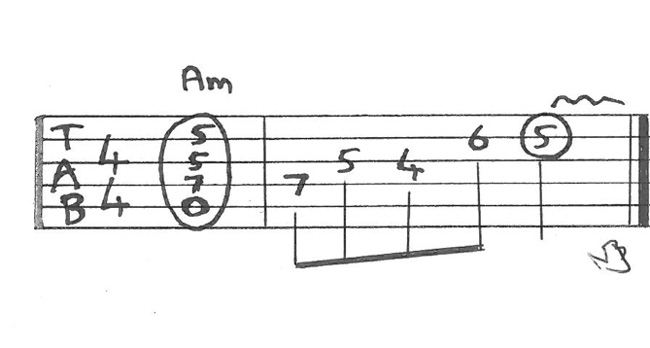

To this end, this is how Dime would work out simple diatonic third harmonies. We’ll do it via the simple 5-note A natural minor run shown in figure 6, with an A minor chord played first to get your ear in “A minor mode.”

Figure 6

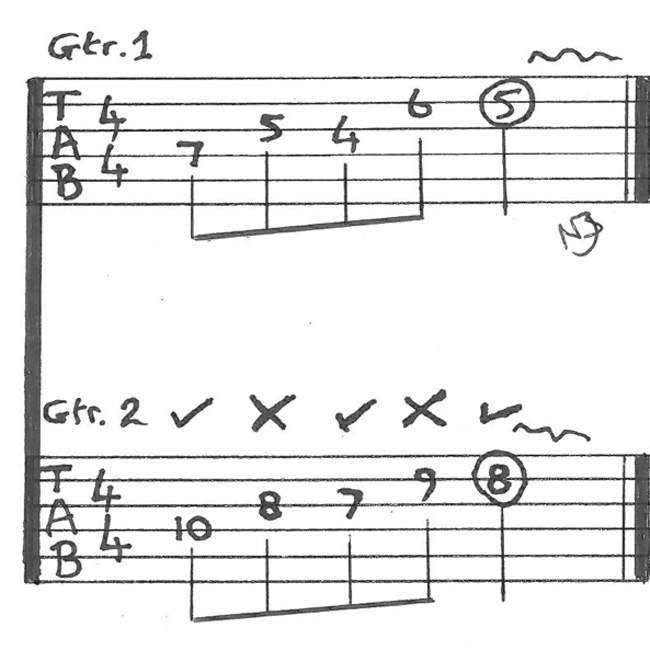

He’d record that on his trusty 4-track machine and then play the exact same fretboard pattern but three frets (a minor third) higher over it. Figure 7 shows the two parts played in unison.

INSERT FIGURE 7

Figure 7

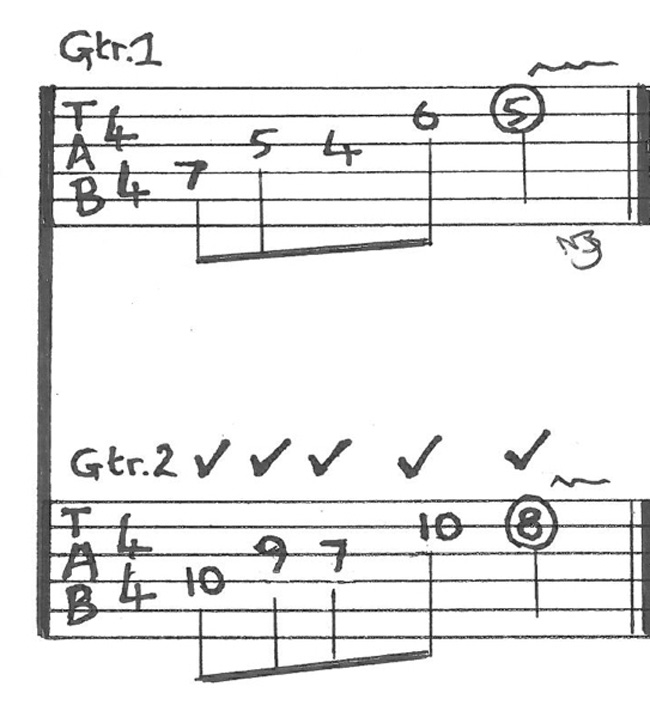

He’d then listen to see which notes sounded good and which sounded bad — these are marked in figure 7 with either a tick (✔) for “good” or an “X” for “bad.” Then to fix the “bad” ones, he’d merely move up a fret (making the interval major), and all would be good. Make sense? Figure 5 has already told us that each diatonic third interval here is either minor or major, so he’s merely converting the “bad” sounding minor intervals to majors. Case closed! Figure 8 shows the resulting “fix.”

Figure 8

Conclusion, Sign-off, and “What’s Next?”

Hopefully this article and video pairing has proved to be a useful and easy-to-understand introduction to the world of Iron Maiden–style harmonies via diatonic thirds. There’s obviously a bunch more to explore (fourths, fifths, octaves, 3-part harmony, yadda, yadda), and we’ll get to that in Part 2 and Part 3, which will follow.

Until then, take what you’ve learned and come up with some dual-guitar harmony ideas of your own. And you don’t need a looping pedal or a fancy, high-tech recording device either. As long as your phone can record, just tap your foot, play the line you want to harmonize, and then experiment over the playback.

Also, I heartily recommend you listen to bands such as Thin Lizzy and Iron Maiden, as both tastefully use diatonic third harmony lines really, really well. Plus the songs are great too!

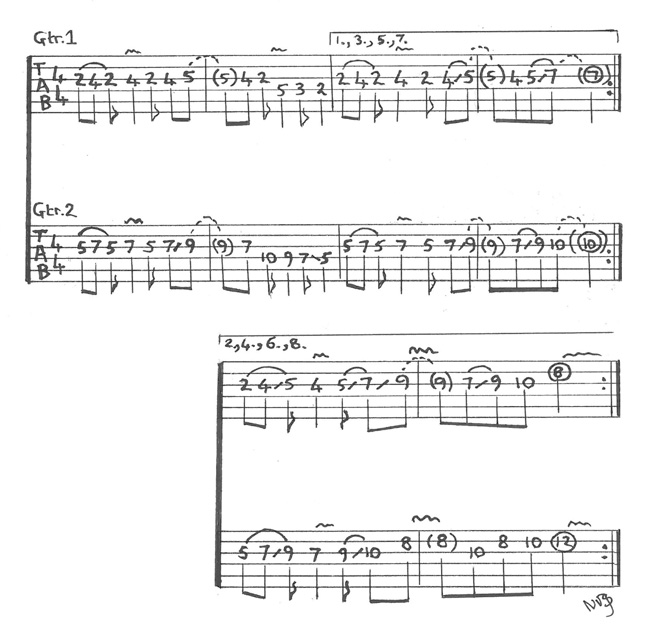

To close, here’s a transcription of the dual-guitar harmony used in the video. The key? C’mon — A minor, of course! Gtr. 1 plays the 8-bar A natural minor melody once by itself, and then Gtr. 2 enters at 7:59 in the video with the diatonic third harmony part.

Until next time, have fun with this.

Figure 9